Photography as Misunderstanding

“Photography is less an objective reflection of reality than a flawed, distorted creature” Li Zehao reveals how Tunnel Wandering(2023) embraces misunderstandings of photography to uncover another kind of reality

Guest Zehao Li Interviewer Edgar Zhang

This interview is orginally conducted in Chinese, Chinese version is available at the end.

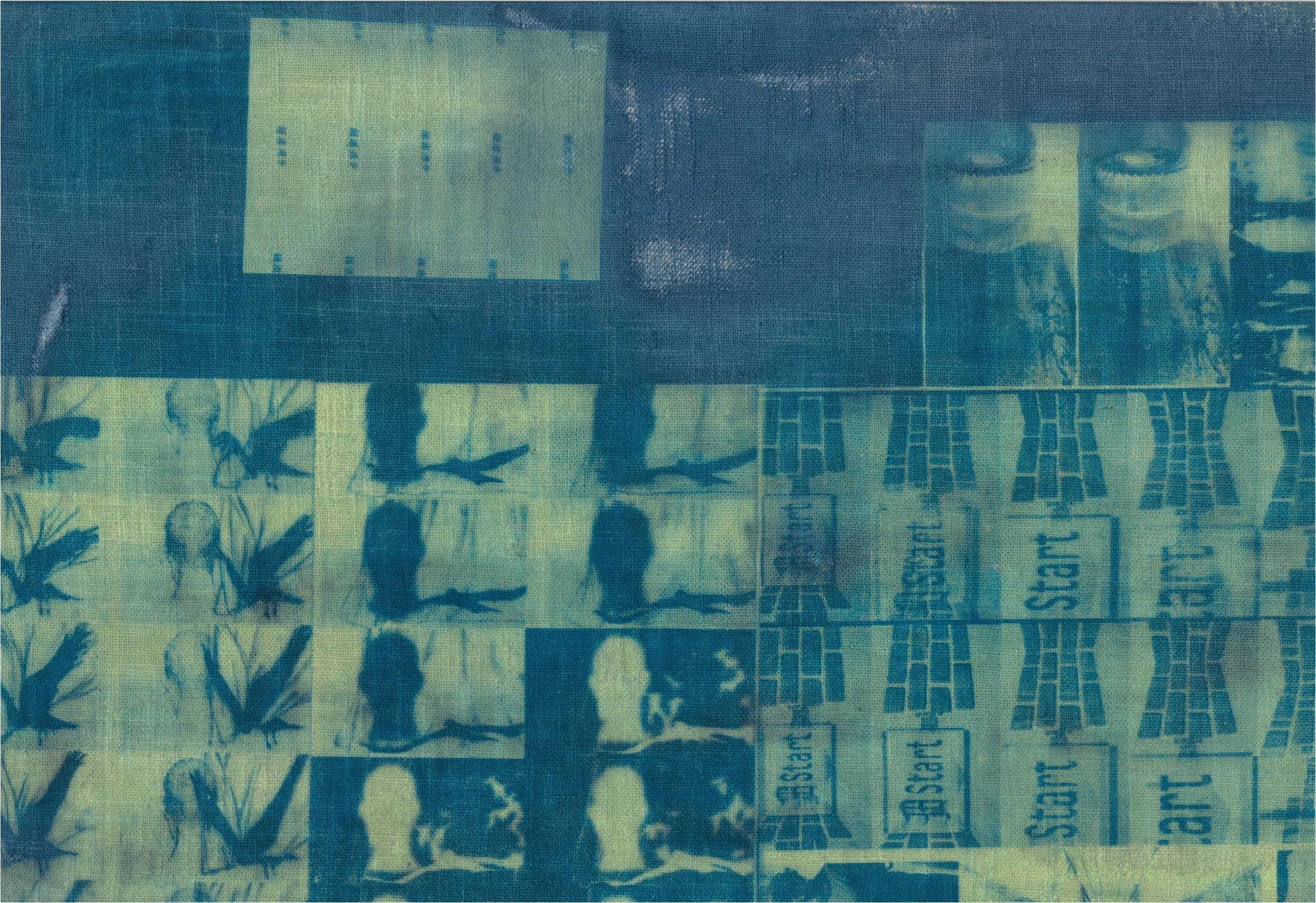

Poster for Tunnel Wandering(2023), Courtesy of Li Zehao

In Li Zehao’s work Tunnel Wandering, dream and photography are placed on the same creative axis. One is the product of the subconscious; the other is a medium with strict procedures and a tangible physicality. Though they might seem parallel, the two constantly infiltrate and intertwine within the process.

The inspiration for the work came from a recurring dream: before the final door, a giant woman kept asking questions until the dreamer changed their way of thinking and gave the correct answer, yet upon waking, the answer completely disappeared...

This conversation between Yitong and Li Zehao moves from dreams to the red light of the darkroom, from the endlessly magnified frames in Blow-Up(1966) to the uncertainty of cyanotype, and to those unspeakable truths and silences that surface when hovering between image and language.

Yitong: When I first watched Tunnel Wandering, it gave me an impression: a very private, blurry dream, as if it surged up from deep in the subconscious, not entirely governed by logic or language. I’d like to begin with that starting point, when you began conceiving Tunnel Wandering, what was the first thing you grasped onto?

Draft for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

Li Zehao:Tunnel Wandering is my graduate thesis work. The key words I gave this piece are dream, subconscious, expression, photography, and truth. Among them, the one I thought about most consciously, and which became the most important—was the relationship between photography and truth.

After watching Blow-Up(1966) from Antonioni, I couldn’t forget the moment when the photographer repeatedly enlarged and developed his photos, and eventually discovered evidence of a murder. The act of developing photos carried a strange allure that fascinated me. I tried to analyze the source of this allure, so I went to a darkroom to learn film development myself.

Only after fully understanding the process did I realize: every step in development can itself become part of creation. A photograph isn’t fixed once it is shot. I also began reflecting on the relationship between photographs and truth, precisely the question Antonioni raised in Blow-Up. Can a photograph really reflect the truth?

To me, photography is less about “recording” and more about “misunderstanding.”

So I chose to simply become a “failed” photographer. Following my interest, I began to notice the subtle connections between my dreams and photography. The idea of using photography to capture dreams gradually emerged.

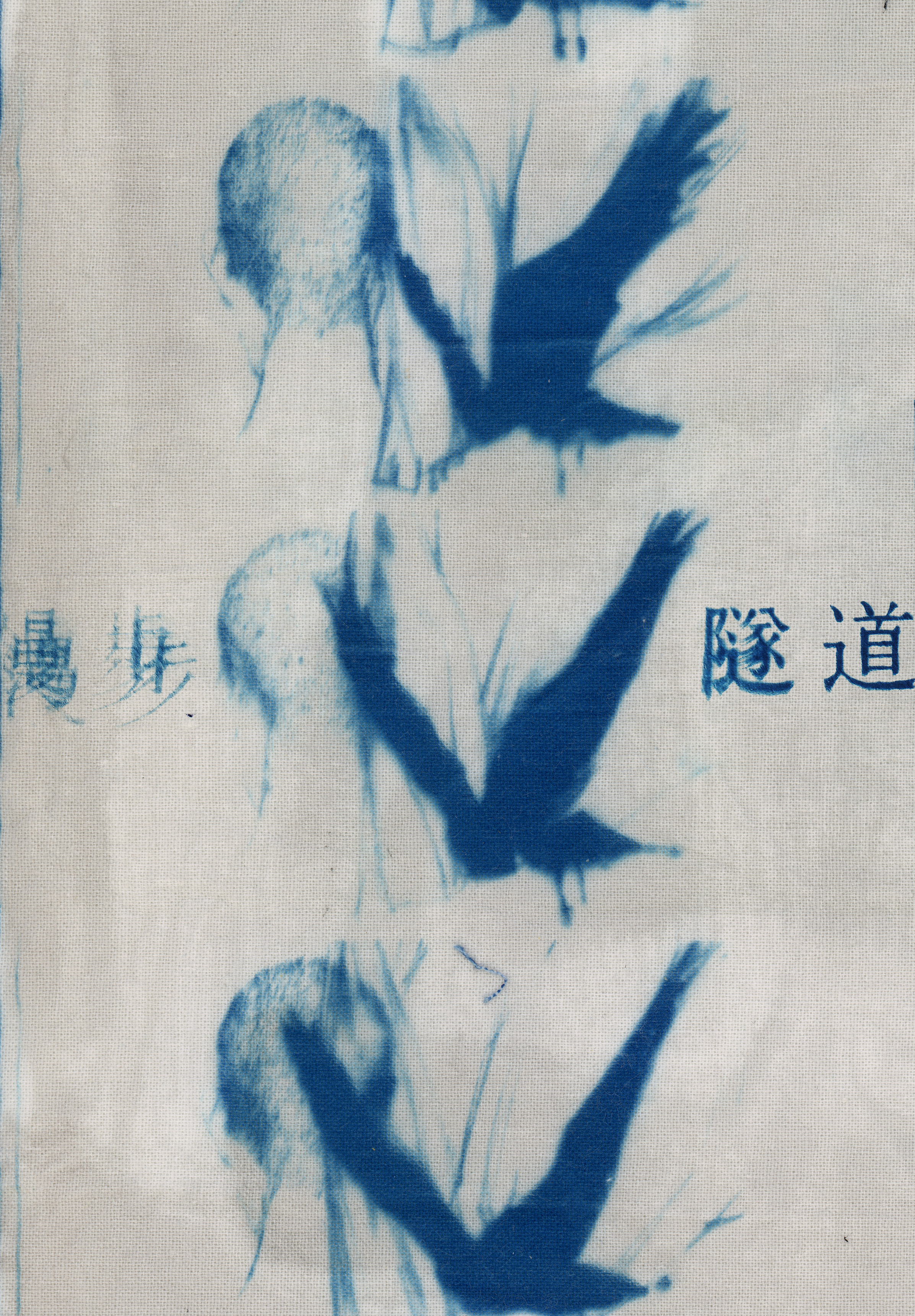

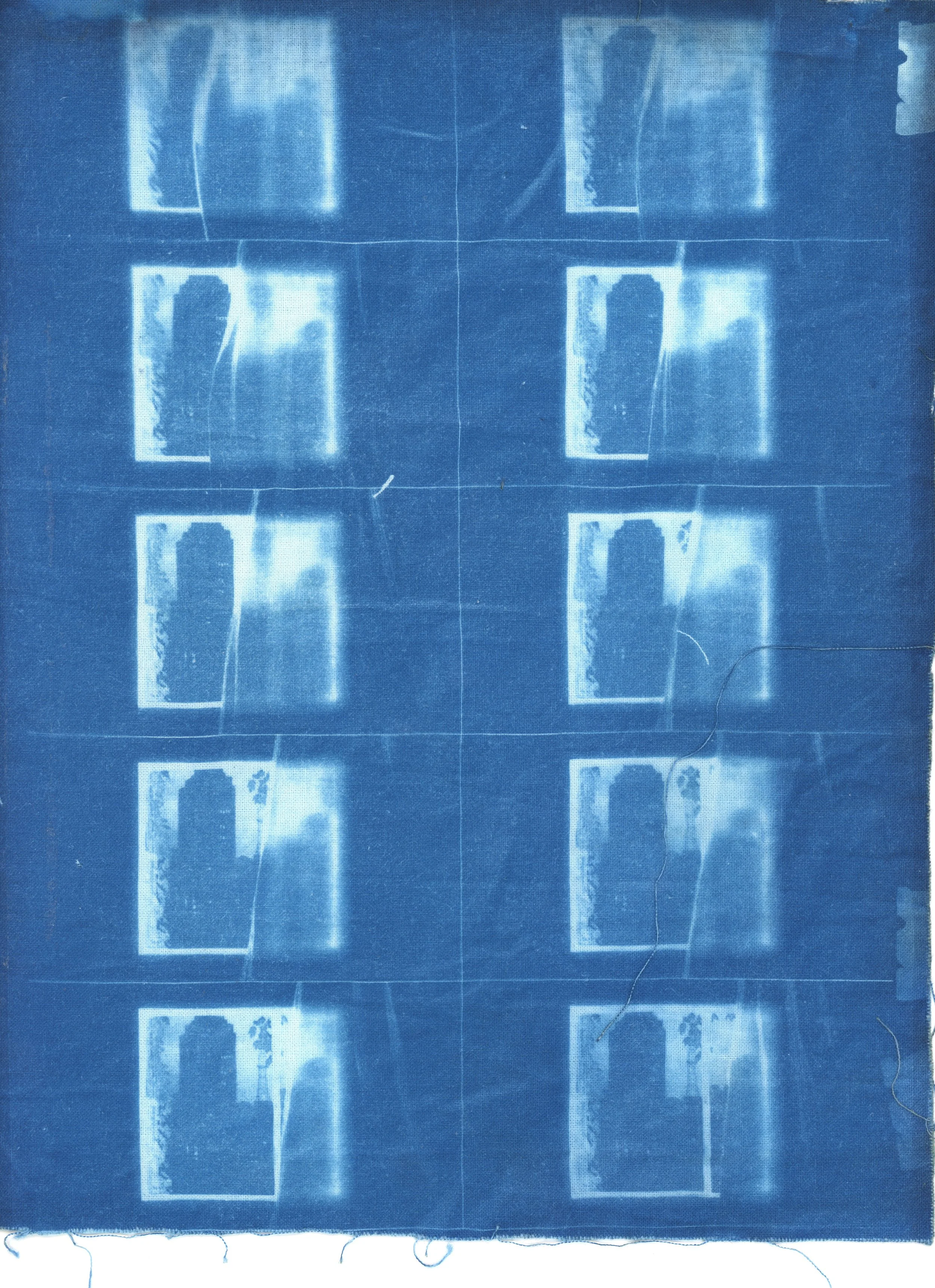

I chose cyanotype, an early photographic technique. Compared to film development, cyanotype is simpler and easier to use, making it more adaptable for animation. I transferred images, whether hand-drawn or photographed, onto paper or cloth using this method.

Since cyanotype relies on ultraviolet exposure, the results depend on the duration of sunlight exposure, as well as weather conditions. At first, I didn’t fully understand the technique, so I produced many “failed” samples. But after some time, I began using these “failures” deliberately, choosing certain papers, inserting tracing paper or foam sheets in between to create blurred exposures, and so on.

Dream and photography may seem utterly opposed, yet they somehow became deeply connected.

The relationship between truth and falsity feels dialectical. We often say dreams are unreal, ephemeral; yet we also say, “daytime thoughts bring nighttime dreams,” as if dreams reveal truths we refuse to admit. Photography, conversely, is said to record truth—photos and videos are often treated as evidence. Yet we also say things like “the sunset doesn’t come out in photos,” or “she looks better in person.” With AI, Photoshop, beauty filters, these “records” no longer guarantee truth. Photography creates a world of images—another world, another kind of reality.

Yitong: You used a very interesting metaphor here: photography as “misunderstanding” rather than “recording.” That’s the opposite of the common perception, where photos are taken as evidence, as witnesses to truth. But instead of pursuing “proper exposure,” you deliberately retained what might technically be seen as failed images, underexposed, pale, lacking in detail. I feel you’re using failure to open another mode of seeing, showing us what “shouldn’t exist” in reality. Could you say more about how you view photography, both as a medium and as a “misunderstanding”? Could you expand on your point that “a photograph isn’t fixed once it’s shot”?

Li Zehao: Photography begins with capturing an image (shooting), then developing the film, producing the image, and printing it. Photography is originally a complex, lengthy process. But as technology advances, the steps from shooting to obtaining a final image have become increasingly simple. Without experiencing the complexity and slowness of that original process, its mystery is kind of lost.

We must notice:

From the moment the shutter is pressed to the final image, no step is perfect or absolute. Photography is essentially a translation of reality, a paraphrase of the real. Every step is uncertain, so the final image is less an objective reflection of reality than a flawed, distorted creature.

Of course, “flawed” and “creature” here carry no negative meaning. This is where photography’s mystery is born. The long chain of processes produces a “misunderstanding” attached to the original image of reality. But what exactly is that attachment? In other words, those blurs, afterimages, contrasts, and colors—things that don’t belong in reality—what allows them to exist?

Blow-Up(1966). Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/Bridge Films

In Blow-Up(1966), the protagonist repeatedly enlarges and develops the photos. Through this process, the image gradually points toward a possible fact: a murder occurring at the scene. But more than the discovery of murder, what fascinated me were the scenes of him repeatedly developing and hanging the prints, scrutinizing them on the wall. I always felt something more terrifying was happening: as the images were enlarged, when they nearly lost all informational content, the photo revealed itself. And just as it was about to lose meaning altogether, the photographer found the hand holding the gun.

What chills us is not the murder itself, but the endless magnification that draws us toward the abyss of the image. The murder serves merely as a timely interruption, in other words, it saved us.

If we were to endlessly magnify a photo, what would we find?

One answer: nothing. We’ve all zoomed into photos on a screen, at a certain point, only meaningless pixels remain, and the act of looking hits a dead end.

Another answer: the more we enlarge, the closer we get to that “something attached” to the original image. We find the mosaic, the noise, the grain, the glowing diodes of the screen. The more we magnify, the thinner the image’s information becomes, and the more the medium itself stands out. Like Plato’s cave, we suddenly glimpse the cave wall behind the illusion.

So in my exploration of photography, I try to emphasize the medium itself. This meta-structural reflection is not only about aestheticizing errors or material textures, but about “an expression of expression”: looking at the other side of the screen, we can only see ourselves gazing back. This visual labyrinth has no exit.

Yitong: Many viewers said they couldn’t understand the film at all. What do you think about that?

Li Zehao:

Draft for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

That relates to the other three key words: dream, subconscious, expression.

It wasn’t until near the end of production that I realized what the film was actually about. The text of my work came from a recurring dream: I was before the final door, answering a giant woman’s questions. I kept answering, but always wrong. At last, I changed my way of thinking and easily gave the right answer. At that moment, I felt I had uttered the truth of everything. But upon waking, I could never recall that answer.

Driven by this pursuit of “truth,” I began making the film. But I was lost in both content and expression: I couldn’t recall the most crucial answer, nor could I understand what the dream’s elements meant. I didn’t know why it compelled me so strongly that I had to make a work out of it.

Draft for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

Amid this confusion, I struggled technically too. It was my first time using cyanotype, and I faced many difficulties and failures. I forced myself to calmly accept the distortions and blurs of the developed images. I wanted to speak truth in the film—but does objective truth really exist? And if it does, am I capable of speaking it?

“I reach out to touch the wind, but only touch the shape of myself.” Gradually I realized, what I wanted to express was not an objective, universal truth, but my own truth. So I turned toward my own obstacles of self-expression. Whenever I speak about myself, I fall into long silences, or can only utter fragmented, incomplete words. This silence covers me like night. Why silence? Perhaps it comes from past experience and trauma. I want to voice my truth, but I can never find the right words. And once truth is put into words, it seems to dissipate like wind.

Dreams are the fulfillment of desire. From that perspective, by breaking through defenses, I finally spoke my truth in the deepest part of the dream. And there, a maternal, naked (real) listener awaited me. She knew everything. She understood why I answered wrongly to protect myself. She was not alarmed; she guided me to speak to myself.

This is, indeed, a very private, personal work. And as I said, I face challenges in expressing myself. But through this process, for the first time, I allowed consciousness to capture and understand the subconscious through the expression of a dream. For me, that was a great comfort, and the true value of the work.

This interview is orginally conducted in Chinese:

摄影的“误解”

“摄影并不是现实的客观再现,而是一种有缺陷、带着扭曲的生物。”

在《隧道漫步》中,李泽昊谈到如何通过这些看似失败的影像与误解,让我们看见另一种可能的现实。

Guest Li Zehao Interviewer Edgar Zhang

Poster for Tunnel Wandering(2023), Courtesy of Li Zehao

在李泽昊的作品《隧道漫步》中,梦境与摄影被放在了同一条创作轴线上。一个是潜意识的产物,带着无法完全用语言捕捉的情绪与影像;另一个是有着严密流程与物理质感的媒介实践。本应平行的两者,却在创作中不断相互渗透、交错。

作品的灵感源自一个反复萦绕的梦:在最后一扇门前,一个巨大的女性不断发问,直到梦者改变思路,说出正确答案——然而醒来后,这个答案却彻底消失... 本次对谈由 Yitong 与李泽昊进行, 我们从梦境谈到冲洗暗房的红光,从《放大》里不断被放大的画面谈到蓝晒的不确定性,也谈到在影像和语言之间徘徊时,那些难以启齿的真理与沉默。

Yitong: 当我第一次看《隧道漫步》时,他给我一个画面:一个很私密、很模糊的梦境,它像从潜意识深处涌上来,不完全被逻辑和语言掌控。我想先从最初的那个起点问起——在你开始构思《隧道漫步》的时候,你最先抓住的是什么?

李泽昊:《隧道漫步》这个作品是我研究生阶段的毕业作品。我给这部作品的关键词是梦、潜意识、表达、摄影与真相。

而其中我在意识层面思考得最多、也是最重要的关键词是摄影与真相。

我在看完安东尼奥尼的《放大》后,久久无法忘怀的一点是,摄影师主人公一遍一遍地放大并冲洗照片,并最终在照片中发现了一场谋杀案的场景。冲洗照片这一行为有一种神奇的魅力吸引着我,我试图去解释分析这种魅力的来源,于是我自己去了一间暗室去学习胶片冲洗的方法。

在充分了解了胶片冲洗的过程后我才发现,原来冲洗的过程中每一个步骤都可以成为创作的一部分,照片并不是在被拍摄完后一切就被固定了的。我也在不断地思考照片和真相之间的关系。这也是安东尼奥尼通过《放大》提出的问题。照片能够反应真实吗?

我觉得摄影比起“记录”,更像是一种“误解”,所以我选择干脆做一个“失败”的摄影师。抱着对摄影的兴趣,我开始发现我的梦和摄影之间的微妙联系,用摄影捕捉梦境这一想法,也慢慢产生了。

我选用了蓝晒这一古典的摄影技法,相比于胶片的冲洗,蓝晒的冲洗步骤更简易方便,易于动画的制作。我把或手绘或拍摄的图像素材通过这一技法转印在了纸上或者布上。

因为蓝晒主要是通过紫外线来进行曝光的,所以需要通过控制暴露在阳光下的时长(包括天气等因素)来控制最后的效果。最开始的时候我也不太了解这个技法,所以做出了很多“失败”的样稿,但是在尝试了一段时间后,我开始利用这些“失败”的因素,包括对纸张材料的选取、用硫酸纸,泡沫纸隔在中间进行模糊曝光等等。

梦与摄影这两个似乎完全对立的事物,但又似乎在冥冥之中互相关联起来了。

Draft for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

真实与虚假的关系好像是极其辩证的,我们总是说梦是如此的虚幻与不真实,但也会说日有所思夜有所梦,好像梦会在不经意间显露出我们不愿承认的真相。我们总说摄影记录真实,照片、录像也往往被视为证据,但也会说晚霞的颜色拍不出来,她真人比照片好看这类的话。ai、p图、美颜,这些技术也使得这些记录好像不再是真实的标准。摄影创造了图像的世界,那是另一个世界、另一种现实。

Yitong: 你在这里用了一个很有意思的比喻, 摄影是“误解”而不是“记录”。这和大众对摄影的认知是相反的,很多人会把照片当作证据、当作真实的见证。但你不仅没有追求所谓的“正确曝光”,反而刻意保留那些在技术上可能被视为失败的影像:曝光不足、色调苍白、细节稀薄。这让我觉得你其实是在用失败去打开另一种观看方式,让人看见影像中那些“现实里不该存在”的东西。能不能更具体地谈谈,你怎么看待摄影,无论是作为媒介还是“误解”?您可以展开说说“照片并不是在被拍摄完后一切就被固定了的”这一点吗?

李泽昊:摄影远不仅仅是照片…从获取图像(拍摄)开始,到胶卷的冲洗,照片的显像,印制。摄影本是一个复杂的步骤,然而随着技术的进步,从拍摄到获得最终的照片图像的过程变得愈发简单了。但若不体验这原本复杂且漫长的过程,摄影的神秘便无从显现了。

我们应当注意到,从最初的按下快门,到最后的显像步骤,中间没有一个步骤是确切而完美的。摄影的本质是一种图像的翻译,一个对现实文本的翻译与侧写。它的每一步都是那么的不确定,以至于最终的图像,与其说是对现实的客观写照,倒不如说是一只满是错误的畸形怪物。

Still for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

当然,这里的“错误”与“怪物”完全没有贬义的意思。摄影的神秘也因此而诞生。经历漫长步骤而得来的是对原先现实图像的“误解”,这份附着在原先客观的现实图像上的东西到底是什么呢?换句话说,那些现实中本不该有的模糊,虚影,对比,色彩,以至于最终让人们无法通过照片自身去辨认的现实的图像,它们究竟凭借什么而存在?

Blow-Up(1966). Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/Bridge Films

《放大》中,摄影师主人公一遍一遍地放大并冲洗照片,在这个过程中,图像慢慢接近了一个可能的事实:在照片拍摄的场景中正发生着一场谋杀案。然而比起这个照片中被发现的秘密,主人公反复地冲洗照片,反复地将显像完成的照片挂在墙上仔细审视的场景更吸引我。我总有一种奇怪的感觉:在这个过程中,发生了一些比一场谋杀更惊人,更可怕的事实:在图像的不断放大,以至最后放大的图像中已经很难再辨认出什么信息的时候,图像近乎完全展现了它自身。而就在图像就要失去任何信息的传递的时候,摄影师发现了那个拿枪的手。

真正让人感到毛骨悚然的,并不是谋杀案的被发现,事实上,在不断放大的过程中,我们愈发觉得紧张和诡异了,而谋杀案,只是在恰当的时机阻止了我们掉向图像的深渊,是的,它解救了我们。

如果将一张照片无止境地放大下去,我们会发现什么呢?

一种回答是我们不会发现什么。我们都有过在电脑或者手机上放大照片来观看细节的经历,通常,拉大后的马赛克图像会让我们觉得无用且无聊,好像观看这一行为走到了死胡同,无法从中再获取更多信息了。

另一种可能的回答是:我们越是放大图像,就越是接近上文中提及的“附着在原先客观的现实图像上的东西”。我们会发现马赛克,噪点,纸张的纹理,屏幕上发光的小灯泡…越是放大,作为图像的信息就越稀薄,而承载图像的媒介自身就越发被凸显出来。就像经典的柏拉图的洞穴理论一样,我们在不经意间从幻象中脱出,看见了洞穴的岩壁。

因此,我试图在对摄影的思考和探索中强调媒介本身。这种带有元结构的思考不仅仅是想将那些冲印错误、材料肌理作为质感审美化,也是关于表达的表达:看向荧幕的另一面,我们只能看到凝望着的自己,这个视觉迷宫没有出口。

Yitong: 很多读者反馈了完全看不懂这个影片,您怎么看待这个?

李泽昊: 这就涉及到了这部作品另外的三个关键词:梦、潜意识、表达。

这个影片到底在讲什么,我是在创作接近尾声的时候才明白的。我作品的文本来源于一个一直挥之不去的梦境,我在最后一扇门前回答来自一个巨大女人的问题,我不断地回答,但都是错的。直到最后,我改变了思考的方法,轻松地说出了那个正确的答案,那一刻我感觉仿佛说出了一切事物的真理一般。但梦醒后,唯独那最后的答案我怎么都无法回想起来了。

Draft for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

伴随着对“真理”的追求,我开始制作这部影片。我在内容和表达上陷入了迷茫:我无法回想起那个最重要的答案,我也无法理解梦境中出现的一个个元素所代表的含义。我不明白这个梦为何如此吸引我,以至于我需要做一个作品来呈现它。

伴随着强烈的困惑和迷茫,我在制作上举步维艰,第一次尝试蓝晒技法的我遇到了很多困难和失败,我让自己用平和和接纳的态度面对显影后的一切扭曲和模糊的图像。我想在片中说出真理,但客观的真理真的存在吗?如果存在我又是否有能力说出它呢?

Mindmap for Tunnel Wandering(2023)

“我伸出手触摸风,却触摸到自己的形状”,渐渐地,我明白了,我要说出的不是客观的,普遍的真理,我要说出的是自己的真理。于是我将目光转向自己对自身的言说的障碍上,只要在言说关于自己的事情时,我就会陷入长时间的沉默,亦或是只能吐出无法连成句子的只言片语,这样的沉默如黑夜一般笼罩着我。为何沉默?这或许与过往的经历和创伤有关。我想要说出关于自身的真理,但我总是找不到合适的语言,而似乎一旦成为语言,真理就会随风消散。

梦是愿望的达成,从这点来说,穿过重重防备,在梦境的最深处,我才终于肯说出自身的真理,而且那里是有一个母性的,赤裸(真实)的聆听者。她清楚的知晓一切,她明白我为了自我保护而有意无意回答错误的答案,她并不慌张,她引导我说出自身。

这确实是一部十分私人的,个人的作品。而就像刚刚所说的,我关于自身的表达也存在一些问题。但无论如何,通过这一次制作,我第一次如此深入地通过理解自己的梦的表达,来让意识捕获和理解潜意识的愿望,这对我而言是莫大的宽慰,也是这个作品的价值所在。