The Weight of a Weave

In conversation with Sarah Sense about intimacy, erasure, and the stories held between image and fiber.

Guest Sarah Sense Interviewer Sally Han & Edgar Zhang Writer Edgar Zhang

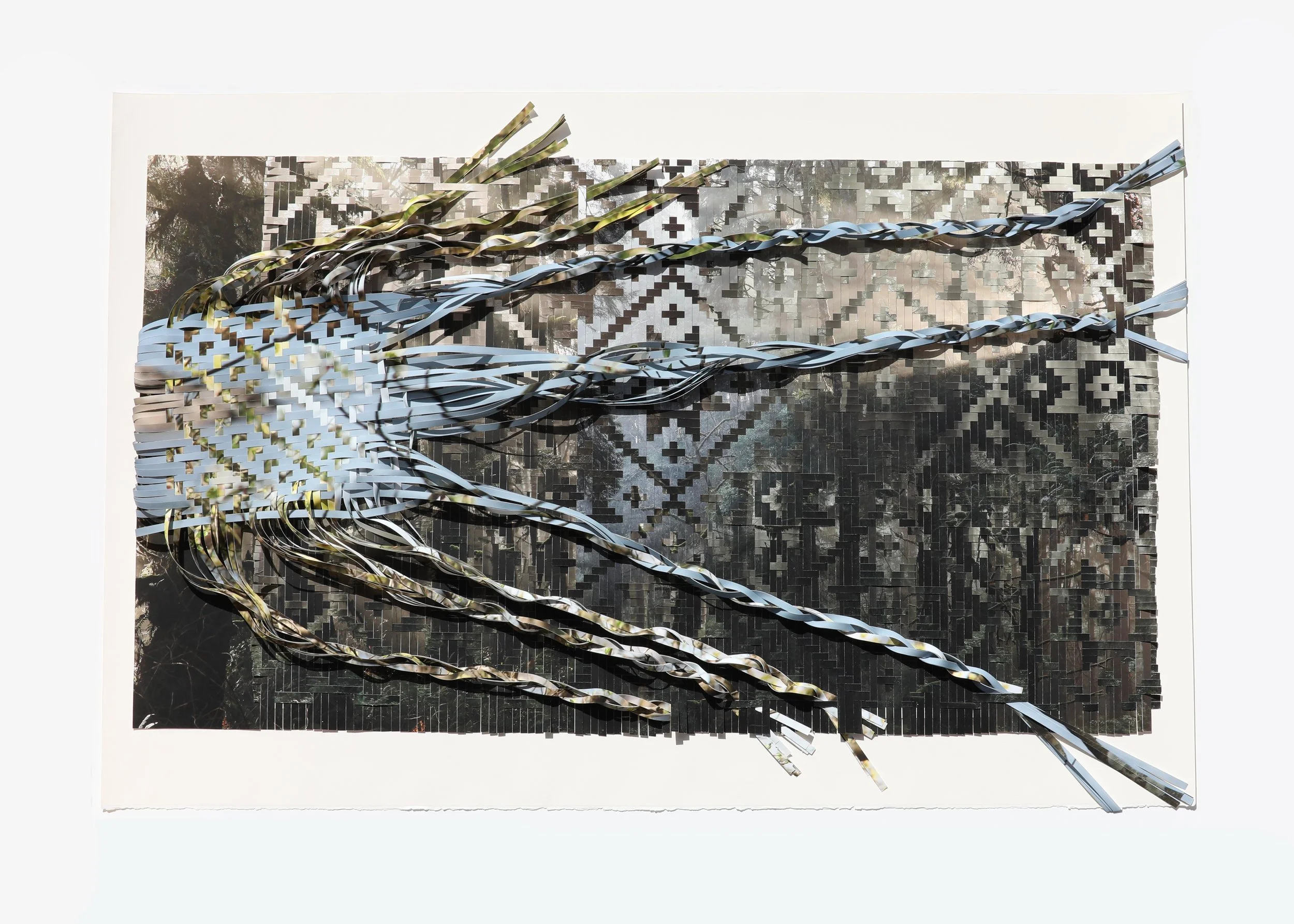

Brooklyn Alligator Study, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

We are honored to have the opportunity to speak with Sarah Sense about I Want to Hold You Longer, a series that resonates with emotional urgency, ancestral memory, and visual precision. The works are both deeply personal and politically charged, blending traditional weaving with photographic imagery and archival material in ways that challenge how we look, remember, and connect.

This interview is an invitation to step deeper into Sense’s process, how the work began, what it carries, and how it is shaped by the larger conversations around identity, land, and legacy.

DART Magazine(Sally): I Want to Hold You Longer is a title that suggests both intimacy and impermanence. What initially inspired the “I Want to Hold You Longer” series, and how did the title come to you?

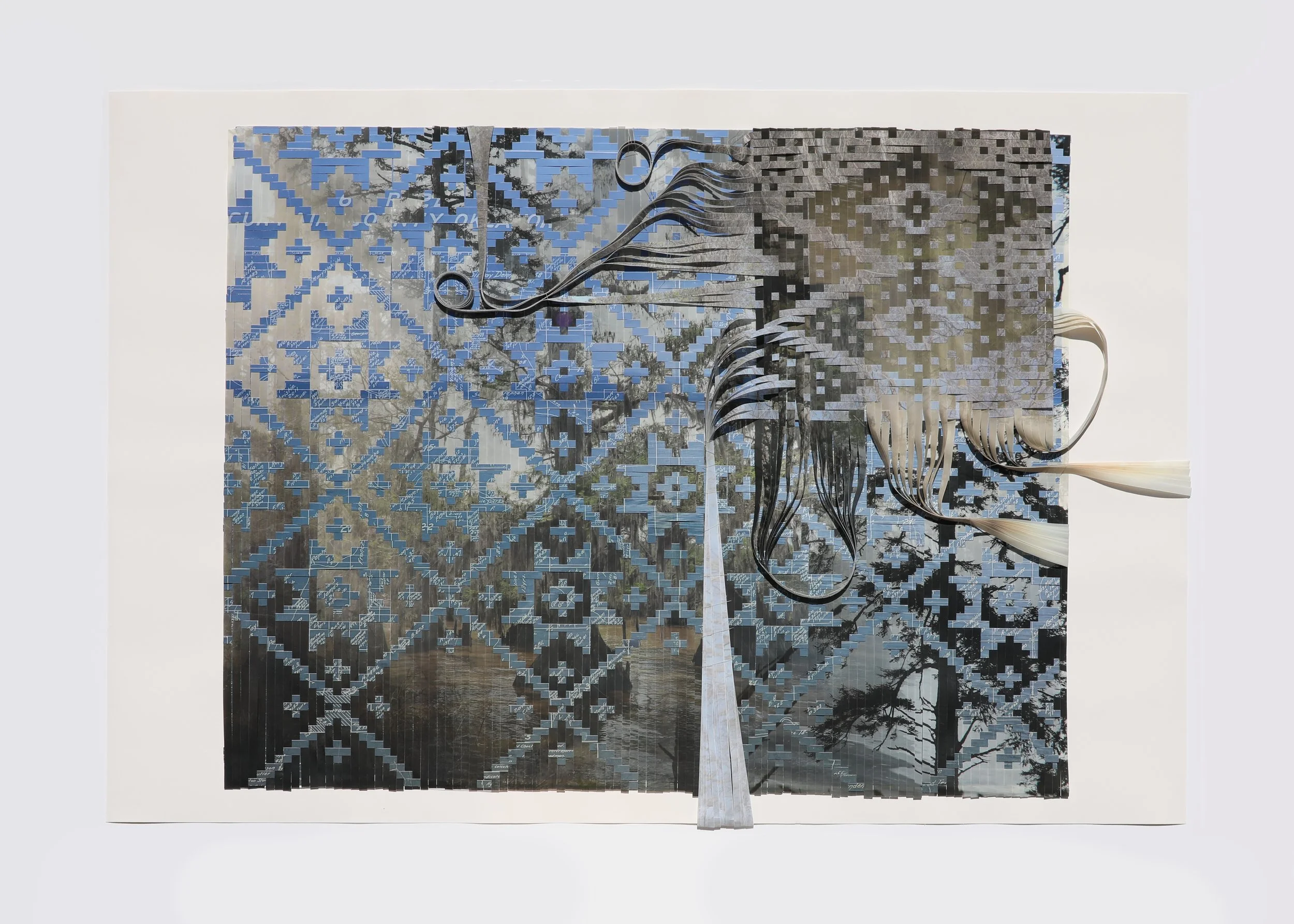

Worcester Bowtie Study, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Sarah: When I was visiting Chitimacha baskets in the archives in various museums and also familial baskets at familie’s homes, I didn’t want to let the baskets go and the saying, “I want to hold you longer,” was coming to my mind. It was an endearing statement that reference ancestry, family, grandmothers and mothers.

DART Magazine(Edgar): In your recent interview, you mentioned the making of the HINUSHI Butterfly, and how it was the first time you braided the strips on a finished piece, and that is something we haven’t seen before. This method is even more expressed in I Want to Hold You Longer, the form of those braids seems to hold on to something, struggling, things happening, somethings are being stressed… There’s this movement compared to other works of yours. Does that relate to the title I Want to Hold You Longer because of the eagerness in this series?

Sarah:

I think the braids reference hair, and in a very personal way, it references me, my sister and my mom.

Further, I see the braids over landscape as a symbol of tying a matriarch to land, bringing forward the idea that we are all connected and more deeply, the matriarch of grandmother-mother-daughter-sister relationships have been significant to me and my upbringing, so braiding or weaving through the landscapes ties a person to place.

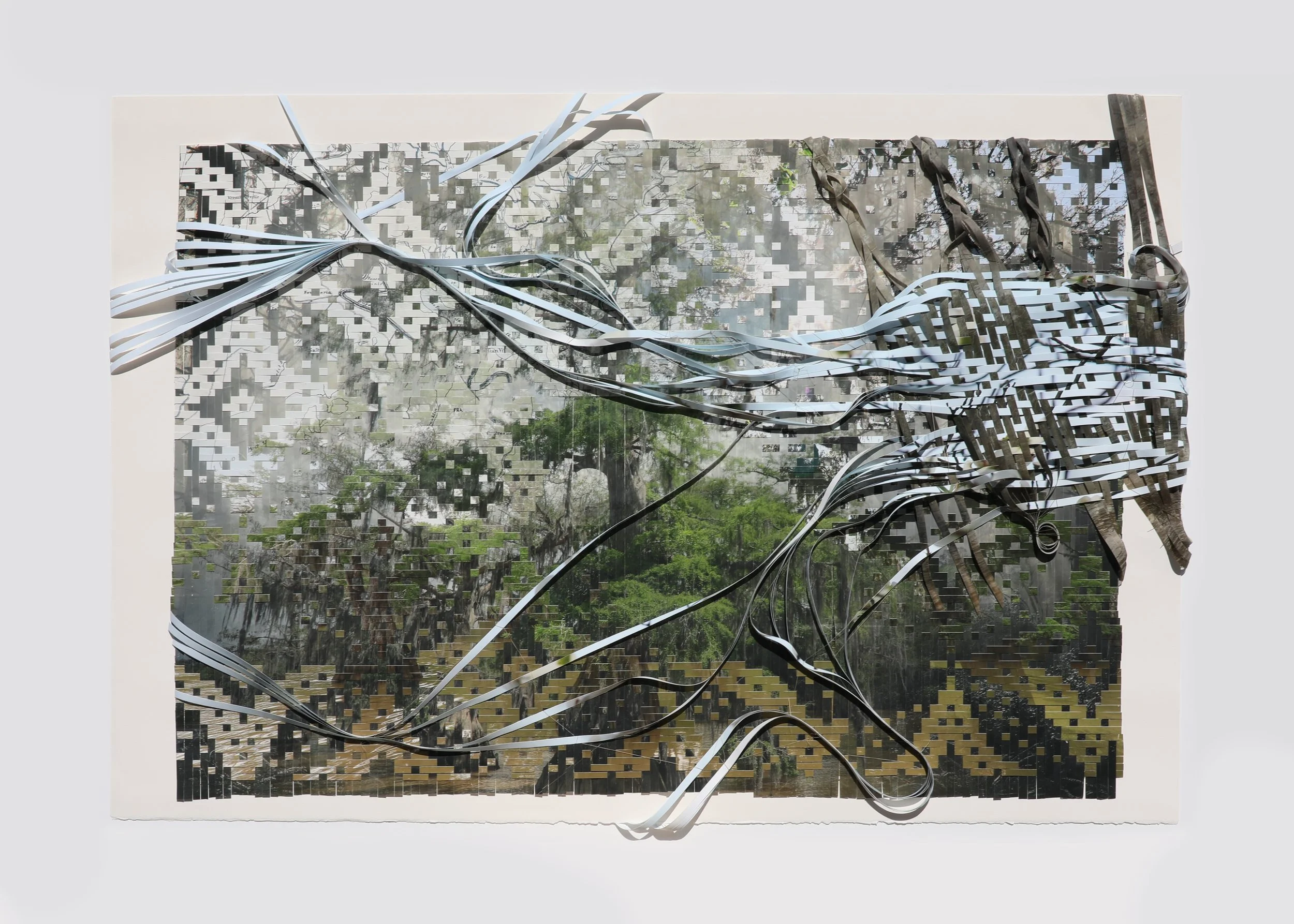

Montclair Mouse, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

DART Magazine(Sally): Your works involve hand-cutting and weaving printed photographs into layered compositions. How do you decide what to preserve, obscure, or reveal in the weaving process? Or another way of asking this: How do you navigate the ethical implications of obscuring certain parts of an image, especially when working with Indigenous memory and land?

Sarah: When working with archival imagery, such as maps, I am presenting history with the intention of story telling. My choices to reveal or cover depends on the story and the ways that I can share information with intention.

Brooklyn Alligator, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Montclair Mouse Study, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

DART Magazine(Edgar): Your work comes across as both conceptually rigorous and emotionally charged, yet it also invites a more critical reading with us…

The woven photo-works present a powerful metaphor: colonial violence is not only remembered but materially embedded in the present. Through slicing and weaving maps, treaties, and archival records into landscapes, your work visualizes the entanglement between land and document, body and bureaucracy. This friction—between traditional weaving as a generative practice and its collision with colonial instruments of dispossession—feels especially poignant, as you once noted: “I saw the joy of weaving in the patterning but also felt the desperation of weaving.”

The conceptual structure of the work seems to be stabilizing into a formal system, we wanted to ask: is there a risk here that the visual strategies (layered weaving, expressive gestures, archival overlay) become a language too easily read—its effect predictable, its critique aestheticized.

The work was beautiful without a doubt, but sometimes that beauty risks neutralizing its urgency. When violence and trauma are turned into texture, would they risk being consumed more as an elegant form than as rupture?

In architecture people often criticize abstracted cultural designs to be made consumable for media, but the other half would argue that does not mean to solve problems, it is already a big effort to bring that idea, culture, story into conversations of media so these issues get more attention like they deserve. Where would you say you stand in that conversation or not at all?

Montclair Perch, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Sarah:

When visiting an archive, I am researching genocidal stories, such as treaties, land deeds, allotment maps, I am aware of the action being more grotesque than the maps as a documentation of warfare. While the information being presented is dark, there is a seduction that lures the viewer.

It is up to the viewer how far to read the image and the meaning. The seduction is present in the archive, with the imagery, the beauty of old books, hand-coloured maps - we can always find aesthetic meaning in things, that doesn’t mean that the content is also beautiful. The seduction of the archive is a tool of beauty to entice the viewer - it is then up to the viewer to read as deep or as shallow as they can. My hope is that it is a combination of both, perhaps to hold attention and then it hits hard once processed, if given the time. I am aware of how quickly imagery is processed and passed by, so I find it a challenge to create something that engages with someone and holds attention long enough to make them think deeply about a concept, idea or history.

DART Magazine(Sally): Your works often depict fragmented geographies and overlapping visual layers—maps, grids, borders, and archival documents. How do these elements speak to the historical systems that have controlled Indigenous land, identity, and movement, such as colonial land seizure, legal classifications, or institutional erasure?

Montclair Eye, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Montclair Eye Study, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Sarah:

Making work with historical, colonial maps is a comment on erasure.

When a viewer engages with the maps and finds new information about the land through historical maps, it points to the position of government and purposeful erasure. These actions of erasing are politically charged, and therefore searching the archive for documentation of unknown histories is also a political statement. Indigenous lands have and continue to be colonized with violence and genocide. It is a horrific history that is being repeated and we are witnessing today through several media outlets. I believe that for this reason, government entities are blocking or preventing historical information of racism and genocide as a means to push current agendas of colonizing. In contrast, the more we can expose about the past will hopefully guide people toward the realities of North America and the violence that we are currently encouraging and inflicting on Palestine, Venezuela, at home with ICE and with other sovereign nations.

Erasing the past or ignoring contemporary Indigenous people in North America is warfare, as a means to manipulate people and disrupt perceptions.

DART Magazine(Edgar): What kinds of responses or questions from audiences have stayed with you since sharing this body of work? Any fun stories to share? We believe the readers would love to hear.

Sarah:

The best part of I Want to Hold You Longer was working with the curators, weavers and community members. It truly was a community project.

The highlight was going to the Montclair Art Museum for a Gala where they honored me and Chairman Melissa Darden. We had other friends, family and community members with us to celebrate. My highlight was viewing the baskets with weaver, Melissa Darden and scholar, Daniel Usner. The baskets really did come to life for us in the archive and we shared that together. It was a true honoring of the ancestors and acknowledgement of what they have given for our present Chitimacha community to thrive.

Worcester Bear, Courtesy of the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery