April 25 2025

Joel Murnan and his Monsters

“Almost every culture has a monster that comes from the landscape and carries qualities unique to that place.”

Guest Joel Murnan

Interviewer Livia Xie & Edgar Zhang

Written by Livia Xie

Editor Edgar Zhang & Livia Xie & Sally Han

Design Edgar Zhang & Meredith Whisman

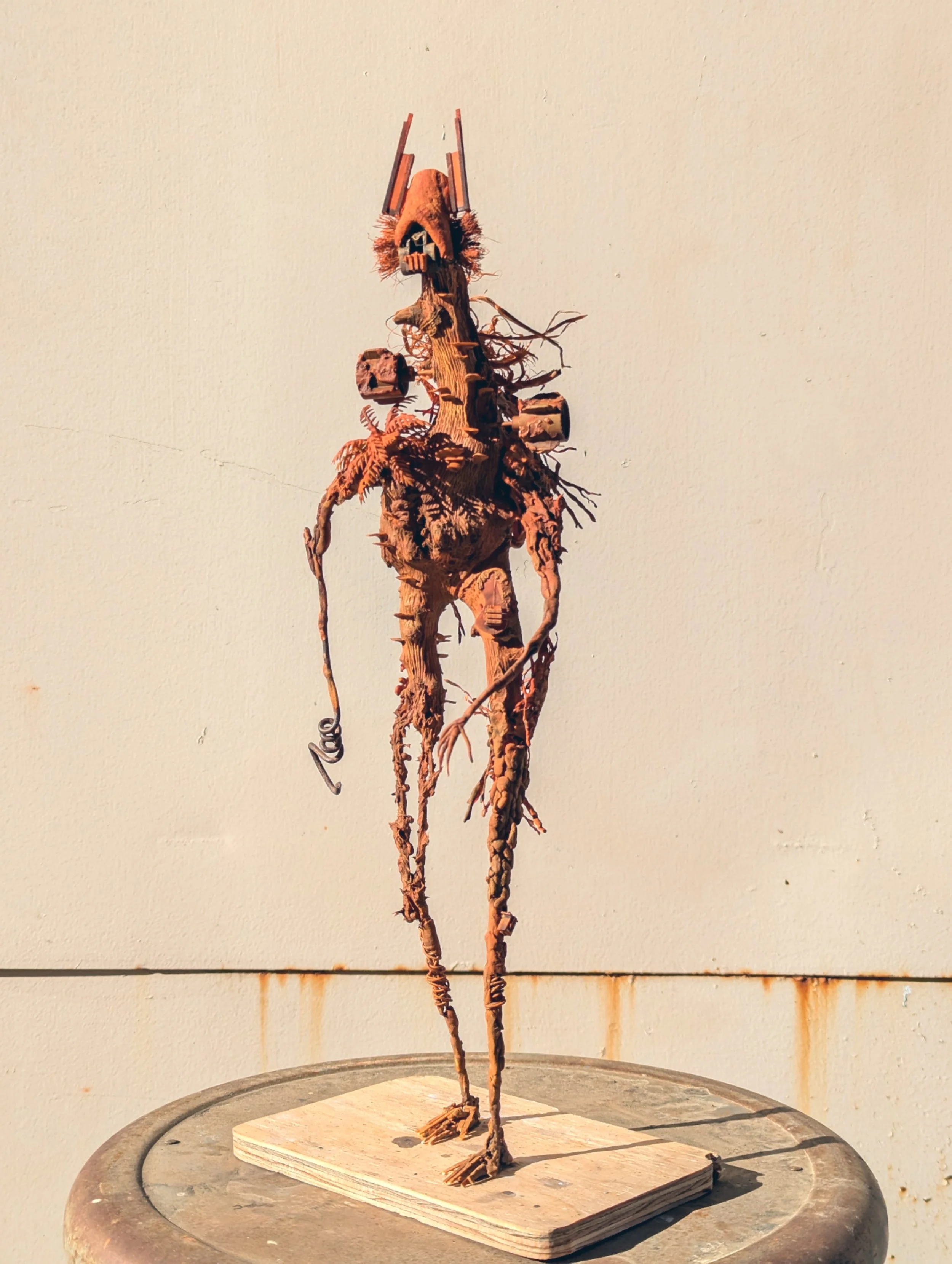

Scarecrow, 48″ x 36″ x 80″, wood, epoxy clay, plaster, foam, LED lights, cardboard, acrylic and found objects

“I grew up about an hour and a half northeast of here, towards Tahoe, there’s a little town called Grass Valley. The countryside there is horse country, wide open and rural. So that plays a big part in my relationship with the landscape. I’ve always tried to take those moments when I pass by—just taking in the landscape and bringing that sense of space back into these works. I kind of build what I see in that way.”

The voice belongs to Joel Murnan, a sculptor and MFA candidate at UC Davis. When my colleague Edgar and I spoke with him on a quiet afternoon in his studio, it quickly became clear how deeply his upbringing has shaped his practice—his stories, like his sculptures, always seem to return to the land.

"When I just came here, to Davis, I was working with this idea of privatization of landscape. I have been super fascinated with how the fence divides our world and creates borders. That's why I brought the fence into my earlier works."

Moving On, 2023, 48″ x 42″ x 13″, Wood, brick, wire, epoxy clay, found wood, plaster, soil, flock, dowels, aluminum mesh

Joel brought us to a sculpture titled Moving On. Its upper half resembles a flawless landscape model. Joel mentioned that members of his family had worked with models, so in a way, sculpture was introduced to him through that medium. But within Moving On, there’s a clear ambition—or maybe even urgency—to tell stories. Emerging from the lower half of the sculpture are monstrous, uprooting forms, as if they're shifting the land and dragging the fences away with them. I can still see a certain monstrosity in it. I almost felt like Joel has stepped beyond the role of sculptor and taken on that of a sci-fi storyteller.

“The fence, to me, is this symbol of privatized land—a history that’s both fascinating and devastating. Everyone should have access to any part of the landscape they wish,but the fence is this reminder that access is limited—it’s like a symbol of a lingering caste system, especially in the States.” Joel explained.

This system is something Joel is always reckoning with, as it prompts him to rethink the relationship between nature and humanity. “In a lot of my work, the scale is miniature, but there’s never a human figure.”

There’s always a presence of absence.

“A part of me finds peace in that—the idea that nature can just exist and thrive without us. But at the same time, we’re part of it too. We are nature.” said Joel, “How do I find myself in all of this? And how do I find our history in all of this? Because there was a time that we were all coexisting, and now it’s shifted so much.”

Joel may have been driven by a search for his role as an artist in relation to nature. Perhaps it was also his curiosity about the natural world or a desire to document its presence through his work. In any case, this led him to begin a series of material experiments focused on trees. He started applying liquid latex onto pieces of bark, making molds that captured the texture and form of the tree’s surface. As Joel described: “I brushed it onto the tree bark and built up layers over several days as it dried. Once it was ready, I could peel it off—and obtain this big, stretchy rubber band, super elastic. Then I poured Plaster of Paris into the mold, so I could create multiples.”

Through this process, tree bark, something as unique as a fingerprint, became a replicable object. To me, this transformation feels particularly absurd, both as a product of technological advancement and as a result of humanity's attempt to tame nature.

Joel clearly excels at using irony in his language. After a few successful experiments, he applied latex to a living Valley Oak tree, ultimately harvesting a large mold. The mold was then cut and filled with plaster, taking the shape of what could be mistaken for an animal hide. When we entered his studio, the "hide" was hung on the wall by the door, like a hunter's trophy—only this time, the victim was not an animal, but nature itself.

Oakhide

Priapus, 95″ x 44″ x 33″, wood, epoxy clay, plaster, foam, LED lights, cardboard, acrylic and found objects

Joel then began to tell us about the other sculpture, called Priapus, which is named after the fertility and agriculture god in Greek and Roman mythology.

“With this piece, it turned out to look loosely figurative, almost like a scarecrow. That got me thinking – scarecrows protect agriculture; they ward off birds and other animals that might attack crops. I’d like to see them as markers of land and borders.” Joel explained.

“So from there, beyond the protective role, I find that there’s also a really scary quality to them, that’s how I fell into ‘the monsters’.” He continued, “That’s where I’ve been focusing lately, I’m now working on these larger pieces, along with the Maquettes’ there that came first.”

Monsters, in the old time stories

Maquette #2.

16″ x 5″ x 5″, wire, plaster wood, sticks, model sprues, spray foam, spray foam spray tip, mandarin bag, roots, epoxy clay, oak gull, card board, plaster, acrylic.

Maquette #1.

9″ x 4″x 4″ wood, wire, foam, epoxy clay, plaster, found objects, mandarin bag, and latex paint

Maquette #4.

14″ x 8″ x 6″ wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, model parts, light bulbs, wire, mandarin bag, flock, acrylic paint.

Maquette #3.

14″ x 8″ x 6″ wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, model parts, copper wire, wire, mandarin bag, lichen, acrylic paint.

Throughout Greek mythology, none of the gods ever punished humans for exploiting or violating the natural world, except Artemis. Even Artemis’s case, often romanticized as a demand for reverence toward nature, is not truly about ecological violation. Her most cited acts of payback — turning Actaeon into a stag after he unwittingly glimpses her bathing, or slaying Orion for attempting to violate her or her maidens — are not about nature at all. They are about the body, about chastity, about sexual violation, consent, and feminine sovereignty.

To read these stories as metaphors for ecological justice is, frankly, a distortion. The offense in each case is not the exploitation of nature but the abuse of a woman. Artemis is used as a guardian of a patriarchally defined purity — one where the violation of a woman’s body is prioritized over the desecration of the earth. These are not stories about protecting nature’s rights. They are stories about punishing transgressions against a social order in which female virtue is sacred only when it remains untouched.

So the absence of mythological narratives where gods punish humans for harming nature speaks volumes. It reveals a fundamental lack of respect for nature in ancient European cosmologies. Perhaps this absence is why monsters had to be invented — to fill the moral void left by those indifferent gods. In the figure of the monster, fear becomes a proxy for reverence. The terror of the creature is what remains when awe has no divine name.

Joel, too, saw a connection between the terror of monsters and human reverence for nature. He shared a similar thought: “Monsters were a way to describe the unknown.”

“I got curious about what a monster is and how it relates to the landscape,” said Joel, “Because almost every culture has a monster that comes from the landscape and carries qualities unique to that place.”

One reference he turned to was Beowulf, an Old English poem he found during his research. In the story, the hero Beowulf is serving a king and helping construct a great hall near the edge of a forest. A monster named Grendel begins attacking the site, and Beowulf kills him. However, it turns out Grendel has a mother, who then retaliates, leading to another battle in which she is also killed. Beowulf is ultimately celebrated as a hero.

What interested Joel was not the plot itself, but what happens when the roles are reconsidered. “It’s interesting when you flip the script – who’s the hero, who’s the villain, or in this case, who’s the monster?” he asked. If Grendel is simply a being responding to an intrusion into his territory, and Beowulf represents a civilizing force pushing into the wilderness, then the story can be read as a metaphor for how human societies seek to control nature. Joel noted that this isn’t an isolated case; similar narratives appear frequently in different mythologies.

When something takes on scary qualities in defense of a human possession, it may be sanctified — named Priapus, the god. But when that same violence is enacted in defense of its own habitat, it is now Grendel, the monster. Divinity or monstrosity — it all hinges on the human narrative, on whether it is controllable or not.

Maquette #5

14″ x 8″ x 6″ wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, model parts, wire, garbage, toy monster truck, mandarin bag, flock, acrylic paint.

“Maybe the monster was one of those things that we created in the stories to instill fear—a kind of cultural taboo that warned against entering the forest and disturbing it, because you didn’t know what might happen.” Joel added, “And now we have no monsters anymore, we’re no longer fearful. We just go in and develop, and there are no repercussions. Back then, if there's an unknown, you wouldn’t just cross that threshold without hesitation.”

His frown deepened as he continued, “I think a metaphor for that now might be how we explore the ocean and discover some strange creature lurking in the depths. We see it and our first instinct is to call it a monster. We don't know its name, we might not even have a photo of it—just stories of what people say they saw. But once we get a photograph, categorize it, and give it a name, it stops being a monster. It’s no longer something to fear, it just becomes a thing. So maybe the monster, in that sense, is a distillation of our societal fears of what we don’t yet understand. And while we still have plenty of fears as a culture, this particular fear is absent now.”

Maquette #6

14″ x 8″ x 6″, wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, model parts, plastic, wire, mandarin bag, wire mesh, welcome mat, cardboard, flock, acrylic paint.

Maquette #6

14″ x 8″ x 6″, wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, model parts, plastic, wire, mandarin bag, wire mesh, welcome mat, cardboard, flock, acrylic paint.

Monsters, in the future

Joel is one of the artists I met who, while being emotionally perceptive, is also philosophical and rational. While many other artists today are more intuitive, Joel is relentlessly analytical.

“I’ve been working with this term called Genius Loci.” Said Joel. “It translates to the spirit of place or the mood of the landscape. I’m interested in how we’re attuned to certain areas and what we pick upon – and I try to grasp and channel that feeling in a lot of these works.”

To access that feeling, Joel turned his attention to the materials, matter, and residues of the place, and to the processes through which they disintegrate, decay, and transform. He sees the world as a state of perpetual flux, that the fundamental elements of all things continue to exist in another form, for example, as atoms.

“The branches will break down and decompose and become soil, the metal bracket will rust and then eventually become dust,” but atoms remain, awaiting a new context. ” By stepping into this process, he actively collects, reassembles and recontextualizes these already deconstructed materials. This is his way of reinterpreting the Genius Loci of the landscape.

Maquettes #7

18″ x 6″ x 5″, wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, basswood, model parts, wire, mandarin bag, wire mesh, cardboard, texture paste, acrylic paint.

The creating process reminded my colleague of Frankenstein, that he couldn’t help blurting out this man-made monster story. But Joel is not Victor Frankenstein. His art isn’t a vehicle for ambition. Instead, he listens to the agency of the non-human materials that others have discarded. In his words, he is “allowing the materials to continue telling the story of the place.”

What moves me is the patience he practices with time, decay, and chance. His work is not about asserting human will, but about making space—for what already exists, for what might emerge.

“These, ultimately, will be shown at the Manetti Shrem Museum for a thesis exhibition. But I think afterwards, I really want to put these outside in the landscape and kind of integrate with the natural world.” Joel told us, “And I can see that trajectory once I graduate, I'm hoping to eventually find ways of allowing these to be homes for other creatures and living things. I'm just interested to see, if I have placed it outside, what will the interaction between it and the environment be like.”

“I had a similar experience with an earlier ceramic project—I made large toes and placed them in a vernal pool. Over time, a bird began using them as a perch to catch gnats rising from the water. That moment stayed with me. It made me want to keep placing my works in natural settings and document what interactions occur.” Said Joel.

Maquette #8

18″ x 6″ x 5″, wood, sticks, epoxy clay, plaster, basswood, model parts, wire, mandarin bag, wire mesh, cardboard, texture paste, acrylic paint.

Although, we can still see some personal imagination of Joel in these monsters. Joel’s monster is no ordinary beast made of flesh, its skeleton is crafted of rusted metals, its figures and limbs are slender and elongated, which preserves a haunting sense of fragility. Are these visual languages intentional? Is it supposed to be a biting irony? Joel answered these questions before I even asked:

“If we take that idea a bit further—is how our soil is now embedded with microplastics. It’s toxic. I would imagine that there's some form of life that'll still live on, and that life will then thrive off of whatever these microplastics are."

These monsters Joel created are, indeed, the lives of tomorrow. As I studied these maquettes again, I saw some as wretched, others bearing an incomplete form, and some resembled emaciated children whose growth had been stunted by hunger. One even appeared as though its intestines might burst from its swollen belly. There’s devastation in it, but there’s also resilience and beauty in it.

“These monsters are what comes from the earth, from the destruction,” Joel said. “They rise from the ground and live off the toxicity we created. That’s what they need.”

Joel’s story is, in many ways, a human effort to understand our relationship with nature: its boundaries, its intimacy, its Genius Loci. It is also a story of fear and kinship between us kids and our mother nature. In a sense, humans and monsters are siblings born of the same womb, part of the same story. Our development has torn the maternal body, colonizing her and erasing many of our nonhuman siblings. These silenced bodies are the displaced ecologies, overlooked by human-centered norms. The monsters, born from our abused mother nature, refuse to disappear. They are “abnormal” bodies, polluted, mutated, hybrid, yet alive, confronting our ideas of bodily acceptability. These monstrous bodies are political bodies, shaped by ecological trauma, pushed aside by anthropocentric ideals, but thriving in what lies ahead.

“Even in all that darkness, there's light at the end of the tunnel. I still believe that the Arcology of this place will evolve. It'll become post-human.”

Guest Joel Murnan

Interviewer Livia Xie & Edgar Zhang

Written by Livia Xie

Editor Edgar Zhang & Livia Xie & Sally Han

Design Edgar Zhang & Meredith Whisman

People also read…

News

April 21 2025

Spoiler Alert: Order, Chaos, and Everything in Between

Unveil Gallery at Irvine is thrilled to present Jean Lowe’s solo exhibition, opened April 18.

On the Wall: Planned Community, 2004 oil on unstretched canvas, 120x170”.

On the Ground: POW Carpet, 2020, housepaint on canvas, 154x83”. Photo courtesy of Unveil Gallery.

Interview

April 11 2025

Her Hair

Identity Through Strands: Hair as Root, Legacy, and Cultural Memory

Hong at work for Bound(2025). Photo by Ryan Waggoner.